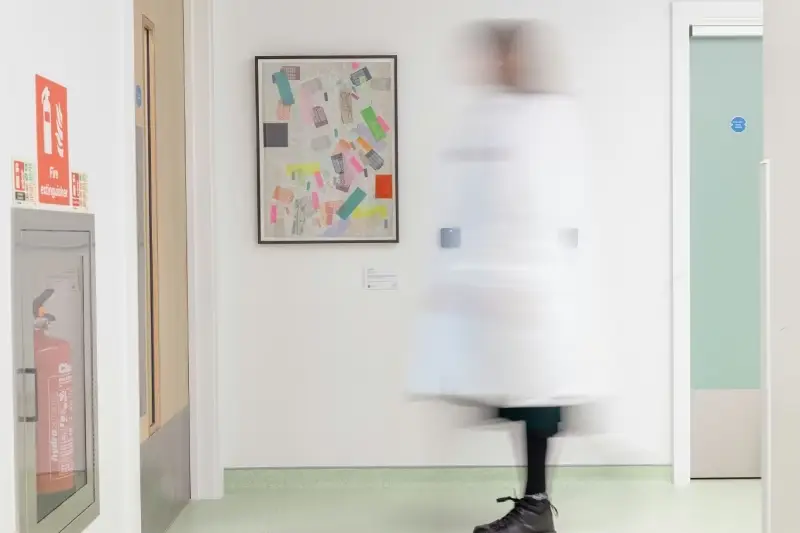

"Yet your energy is not abated" is a department-spanning artwork by J. Yuen Ling Chiu at the CUH Histopathology Lab, 1000 Discovery Drive.

For this commission, Ling has investigated the material practices of histopathology and printmaking to create a body of work about ‘unlocking’. Both the printing template and the biopsy sample are unlocked by the hands of the people who make and study them to reveal the information contained within.

The title is taken from the dedication in Matthew Baillie’s seminal work of 1797, 'The morbid anatomy of some of the most important parts of the human body'. The author is thanking his friend and fellow physician David Pitcairn for tirelessly promoting innovation in medicine to the public.

The artwork throughout the histopathology laboratory has been supported by Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust, with special thanks to Mrs Margaret Midwinter for her generous contribution.

Across the department, the works are divided into three themes: Nurture and Nature, Pasts and Futures, Vessels and Containers.

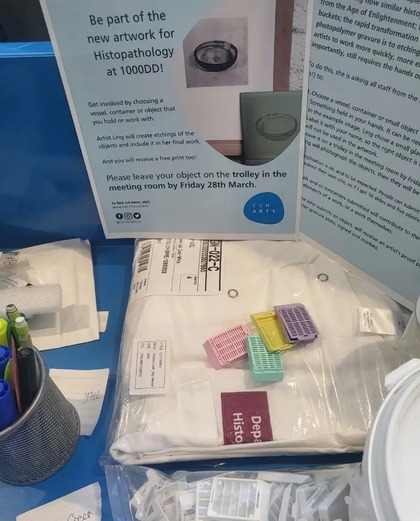

Vessels and containers

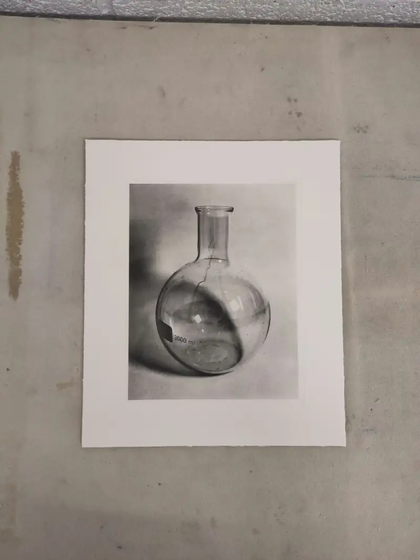

While researching this commission, Ling invited staff members to share a vessel, container or other handheld object they consider important to their work. The result is not just an assembly of objects, but a joyful collection of conversations.

From a beloved coffee cup, to a much-favoured scalpel, to a mega cassette for especially large specimens, to the creation of artwork from excess wax, or the growing of a cutting into a Norfolk Island Pine (used as an Xmas tree), the stories were as varied and diverse as the staff and objects themselves.

In a world that feels increasingly digital and isolated, this work reminds the viewer of the physical experiences and endeavours that are necessary to the human condition.

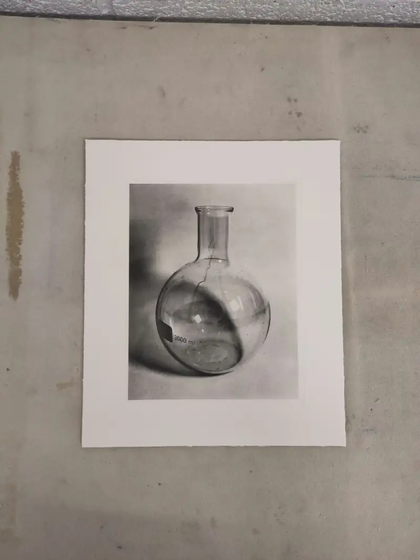

The final artwork is titled (Un)common Vessels and features 31 objects using a contemporary printing technique called photopolymer gravure. This process creates high-quality prints from digital images - the photos are transferred onto light-sensitive photopolymer plates.

“In many ways, photopolymer gravure is to etching, what digitisation is to histopathology – it allows you to work more quickly, more efficiently, and with more scope. But importantly, still requires the hands of the artist to unlock its vast potential.”

J. Yuen Ling Chiu

Pasts and Futures

Histopathology and printmaking share well-established histories, and both are rapidly adapting for the future. This relationship between past and future, is both interesting and challenging.

Both practices are highly skilled, use similar tools (scalpels, dyes, stains, wax, lenses, screens), and embrace technological advances. Most importantly, they both endeavour to look – widely, intently and deeply.

The labs and studios where this work is undertaken are constantly changing. Where there was once a black and white engraving of a specimen, there is now colour, heat, and light. New information is revealed through careful process and thoughtful looking.

Referencing historic and contemporary maps of Cambridge, and comparing the topography to images from slide scans and the electron microscope, a large abstract landscape invites viewers to look more closely.

Other works use UV and heat-activated inks, which only allows the final artwork to reveal itself in response to your action. Just as specialist dyes and inks can help reveal information in a biopsy scan, UV light and the heat from your hands will help the viewer examine a familiar space in a new way.

Ling’s research into the future of printmaking means a commitment to more sustainable practices. Where possible, this includes choosing non-VOC alternatives to solvents; researching new plate and ink technologies; sourcing papers from more sustainable fibres; harnessing digital tools for greater efficiency.

Nurture and Nature

When not looking down at the specimens that make up the daily work of Histopathology, the trees on the horizon of Gog Magog are a focal point of the wonderful view from the labs.

The Royal College of Pathologists estimate that around 20 million histopathology slides are examined in the UK each year. In Ling’s artwork, those slides return as people, finding a space for themselves and each other in the land the surrounds us.

Reflecting on the relationship between caring for an individual and caring for the natural environment, the works create a visual survey of growth, development and decay.

They are abstract or semi-abstract compositions, which build visual landscapes of colour and pattern. Even though the artworks elements are made of many different colours, papers and sizes, the shapes are all the same ratio - that of a glass slide. Abstracted slide-shapes intermingle with plant life foraged from the nearby Gog Magog Hills. Towers look like a precarious pile of work, or slices of individual worlds, of just slides resting or touching the other – balancing together.