Introduction

This leaflet has been written to provide information to parents and families whose baby has been diagnosed with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) and aims to support the discussion you have had with your baby’s consultant and care team.

What is a Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia?

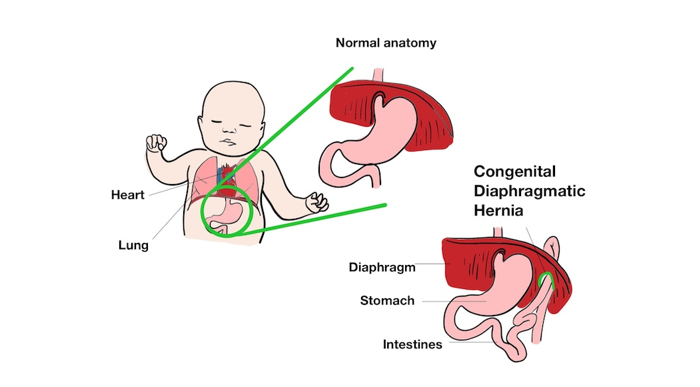

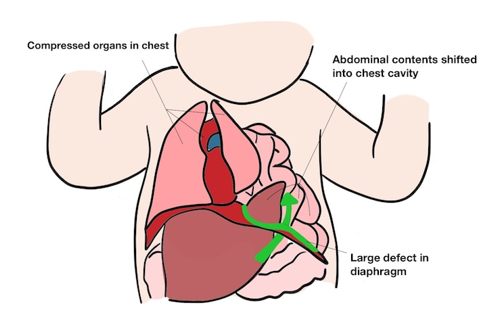

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) is a condition that develops whilst babies are growing during pregnancy. The diaphragm is a sheet of muscle, which usually separates the chest from the abdomen. In CDH this muscle has not formed correctly on the left side in your baby during pregnancy. As the muscle has not formed correctly, bowel and abdominal organs,such as the stomach and liver, can move upward into the chest. In addition, other organs within the chest, such as the heart and lungs, may also be out of their normal position, called ‘mediastinal shift’. CDH affects each baby differently. Sometimes there is only mild mediastinal shift in which the right lung and the upper left lung look normal. However, in some cases the heart, which is usually on the left side, can be pushed to the right side. In severe cases very little lung can be found in the left side, and the right lung may be very small.

Approximately 1 in every 2,500 – 3,000 babies are born with CDH.

The diagram below shows the difference between the normal anatomy of the diaphragm and what happens when the diaphragm doesn’t develop properly.

The diagram below shows the effects of a large defect in the diaphragm, and how chest organs can be displaced/developmentally impaired.

What causes CDH?

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) is a serious birth irregularity, but its exact cause is unknown. In some babies CDH is associated with an underlying syndrome. Your baby will have genetic testing and ultrasound scans (before the baby’s birth if CDH has been seen on an antenatal scan). This will determine if any other abnormalities are present. Unfortunately, not all genetic syndromes can be detected antenatally so we will examine your baby after birth to make sure there are no other issues.

Signs and symptoms

Approximately half of babies with CDH are diagnosed when the problem is seen on routine scans during pregnancy. Other babies are diagnosed soon after being born.

Babies born with CDH may present with:

- Abnormal breathing.

- Rapid heart rate.

- Blue discoloration from lack of oxygen (cyanosis).

- Weak breath sounds (usually on one side).

- Bowel sounds in the chest.

- Concave abdomen and barrel chest.

- Abdominal pain.

- Constipation due to bowel obstruction.

Due to the effect of CDH on the development of the lungs, most babies will need help to breathe after they are born. If the CDH is small, and only the small bowel has moved up into the chest, the growth of the lung on the left side will be impaired but without causing too much pressing or squeezing (called ‘compression’) on the other organs in the chest. However, if there is a significant diaphragmatic hernia, the blood vessels in the lungs don't form as normal and this affects the function of the lungs.

Scans performed before birth can provide a lot of useful information, but we cannot assess how the blood vessels to the lung have developed.

What happens after birth?

If CDH has been diagnosed on antenatal scans, you will be offered a planned delivery and a team of neonatal doctors and nurses will be present at the birth of your baby.

Your baby will be moved to the resuscitaire (a specialized medical cot used in delivery rooms to provide immediate warming, oxygen, and breathing assistance for newborns). We will insert a breathing tube and connect this to a ventilator to help your baby breathe. Occasionally it is not possible to place the breathing tube because of abnormalities in the airway. We will support your baby’s breathing and assess whether there is sufficient functioning lung to sustain your baby outside of the womb.

The team will make every effort for you to see your baby after birth, but it is unlikely that you will be able to hold them because it is important that we stabilise your baby without any delay. Once stable, we will transfer your baby to our Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) to provide intensive support. We will insert a feeding tube (called a ‘naso-gastric tube) and drips, including lines in their bellybutton (umbilical lines) and other lines into veins (long line) to give fluids, nutrition and medication.

After a baby is born there is a sequence of physiological changes which leads to a rapid drop in blood pressure within the lungs. This often does not happen in babies with CDH and results in high blood pressure in the blood vessels that supply the lungs called ‘pulmonary hypertension’. We can treat this with medication, and an inhaled gas called nitric oxide. Occasionally there is a poor response to these treatments. The pulmonary hypertension must improve before we can consider preparing the baby for surgery.

Even if it is possible to achieve good oxygen levels in the beginning, it may become apparent over the first few hours, days or weeks that there is not sufficient lung tissue present to sustain life. We always have open and honest conversations with families about treatment options and finding the right way forward. In some specific circumstances, a heart-lung bypass treatment (called Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygen or ’ECMO’) offered in specialised hospitals in the UK, may be used as a way to support your baby through the first few days.

Feeding babies with CDH

Breastfeeding is encouraged as it has particular benefits for babies. Breastmilk is often much better tolerated than formula. We can often give small amounts of colostrum by mouth from birth, which is both a positive experience for the baby and boosts their immune system. However, feeding is not established until after surgery (see below).

Even though your baby will not be taking breast feeds or breast milk for at least some days, it is important to start expressing breastmilk as soon as possible after delivery and the midwives can help with this. Even if you don’t intend to breastfeed in the long run, it is worth considering expressing breastmilk for the first weeks. Your midwife can talk to you about this.

Treatment and management

All babies with CDH will need surgery. Your baby will need to be stable from the breathing point of view to tolerate the operation. The timing of surgery therefore varies; babies who need less breathing support might have an operation after 48-72 hours, but others only become well enough after a longer time frame. Surgery is most commonly done through an open cut to the abdomen (‘tummy’). Surgery is only undertaken using a keyhole technique if the baby is born at term and has good lung function. During keyhole surgery a number of small cuts are made in the chest wall to allow instruments and a camera to be inserted.

During the operation the organs are moved from the chest, back into the abdomen. The hole in the diaphragm is stitched closed or, if it is large, repaired with a patch. If a floppy diaphragm (‘eventration’) is found, it would be tightened (‘plicated’).

What happens after the operation?

Most babies will be on a ventilator for a number of days after the operation; the exact time depends on how well the lungs are working.

Most babies begin milk feeds a few days after surgery and gradually increase to full amounts. Until full feeds are being given, nutrition will be given through a drip (parenteral nutrition’).

More information about the neonatal unit

Being apart from your baby will be difficult and we will show you how to have positive touch experiences from the start even if a cuddle might not be possible right away. Parents are allowed to visit at all times, but there is limited accommodation available for parents of babies on the Neonatal Unit. We try to provide accommodation around the time of admission, surgery and in preparation for discharge home. If you would like to visit the Rosie neonatal unit prior to delivery, please ask the Fetal Medicine Team to contact Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) to arrange this. A short video introducing the NICU is also available in the Neonatal Services section on the Rosie Hospital website.

Long term outlook

Every baby is different, but generally, the smaller the hernia, the lower the chance of long-term complications. After the operation, unless your baby has an underlying syndrome or has been very sick with periods of prolonged poor oxygenation, children with diaphragmatic hernias usually do not have significant developmental problems.

Longer-term considerations include:

- Recurrence of the hernia – this is rare but would require further surgery

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) – this is where the stomach contents (milk feeds and acid from the stomach) travels back up the food pipe. GORD is common in all babies but can be more problematic in those that have had CDH. Usually this can be treated with medicines but occasionally surgery is necessary.

- Longer term breathing problems – rarely, oxygen needs to be given to babies after discharge when they are at home. Some children who have had CDH are more likely to experience chest infections or asthma. Specialist children’s respiratory doctors will review your child in the outpatient clinic after discharge if there are any concerns about these longer-term breathing problems.

- Scoliosis – this is a curvature of the spine which can develop as children grow.

Support for you and your child with CDH

- Contact a Family (opens in a new tab) is a UK-wide charity providing advice, information and support to the parents of all disabled children - no matter what their disability or health condition.

- The Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Support Charity (opens in a new tab) is made up of experts providing complimentary care to patients and their families in the form of information, emotional and practical support and by conducting, encouraging and funding research.

- BLISS (opens in a new tab) provides support, advice and information for the families of babies requiring intensive care and/or special care. Also works with bereaved families.

Chaperoning

During your child’s hospital visits your baby will need to be examined to help diagnose and to plan care.

Examination, which may take place before, during and after treatment, is performed by trained members of staff and will always be explained to you beforehand. A chaperone is a separate member of staff who is present during the examination.

The role of the chaperone is to provide practical assistance with the examination and to provide support to the child, family member/carer and to the person examining.

Contacts/further information

Paediatric surgery clinical nurse specialist team

Office: 01223 586973

(Mon to Fri 08:00 to 18:00 except bank holidays)

We are smoke-free

Smoking is not allowed anywhere on the hospital campus. For advice and support in quitting, contact your GP or the free NHS stop smoking helpline on 0800 169 0 169.

Other formats

Help accessing this information in other formats is available. To find out more about the services we provide, please visit our patient information help page (see link below) or telephone 01223 256998. www.cuh.nhs.uk/contact-us/accessible-information/

Contact us

Cambridge University Hospitals

NHS Foundation Trust

Hills Road, Cambridge

CB2 0QQ

Telephone +44 (0)1223 245151

https://www.cuh.nhs.uk/contact-us/contact-enquiries/